Historically, horses have been essential to human civilization. Before the advent of steam engines, they were the primary source of power for transportation, agriculture, and industry. Horses played a crucial role in plowing fields, allowing for increased agricultural productivity and food supply.[1] Their strength and endurance made them indispensable in war, where cavalry units played a vital role for centuries. However, the development of the steam engine in the 18th and 19th centuries gradually replaced horses in industrial applications, but their legacy remains embedded in modern terminology, such as „horsepower.“ [2]

Horsepower (hp) is a historical unit of measurement for power that was originally defined to compare the mechanical power of steam engines with that of draft horses. In the classic definition, 1 hp corresponds to approximately 745.7 watts and is calculated as follows: hp= [(550lb*ft)/s]*g.[3] This unit comes with many flaws, such as the fact that horsepower is not the same everywhere. For example, a European „Pferdestärke“ (engl.: horsepower) is apparently smaller (1.36 % less) than an American „horsepower“, which is why Europeans switched to Watts a long time ago. And yet, just as America refuses to let go of their ‚feet‘ and ‚pounds‘, so too does ‚horsepower‘ persist in the car industry.[4]

But before I get to my actual pitch, I’d like to make a brief excursion into the history of the VW Golf 1 (it all makes sense eventually, I promise). The Volkswagen Golf 1, introduced in 1974, marked the beginning of one of the most successful car models in automotive history. Designed by Giorgetto Giugiaro and manufactured by Volkswagen, the Golf 1 revolutionized the compact car market. It was originally launched as a successor to the Volkswagen Beetle, a car that had enjoyed unprecedented success for over two decades.[5]

One of the key innovations of the Golf 1 was its front-wheel-drive configuration, which significantly improved handling and offered more interior space than rear-wheel-drive competitors. With an average fuel economy of around 12.75 km/L, it became a popular choice during the oil crisis of the 1970s, when fuel efficiency was paramount to car buyers. By the time production of the first-generation Golf ended in 1983, more than 6 million had been sold worldwide, making it one of the best-selling cars in Europe at the time. [6]

This transition from horse-drawn labour to mechanised power invites an intriguing question: how does the strength of an 18th-century horse compare to that of a VW Golf 1? At first glance, the idea of comparing a living creature to a mechanical vehicle might seem as absurd as pitting a fish against a human in a footrace. Yet, the very concept of horsepower originated from this type of comparison: The question „If a steam engine could replace horses, how many would it take?“ has been a fundamental starting point in the evolution of our understanding of power and mechanics. However, it also poses an intriguing question: What gravitational force would be required for a horse to match the horsepower of a VW Golf 1 and is there a planet where a horse would have the same horsepower as a VW Golf 1?

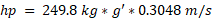

To answer this question, we have to look at the definition of horsepower. The only variable we can change that is not dependent on the horse itself is the gravitational acceleration (g). For simplification, it is assumed that the mass of the horse remains constant, despite an increase in gravitational acceleration. To calculate the new gravitational acceleration, we have to look first at the initial definition of one horsepower and change the units to the metric system, which leads to:

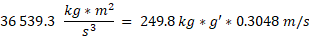

One American horsepower has been defined as 754.7 W. The Golf 1 has 49 hp, which corresponds to 36539.3 W. And 1 Watt is defined as . We now enter this into our equation:

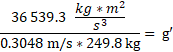

Then we solve for g‘:

Calculated, this results in a new acceleration of 480 m/s2. A planet with 480.6 m/s2 would have a mass and density far beyond that of the known gas giants.[7] To achieve such a high surface acceleration, it would either have to be very massive or very small but extremely dense (similar to a white dwarf or neutron star). This leads to the conclusion: There really is a world out there where an 18th-century horse has the same power as a Golf 1. We just don’t know it yet.

[1] Tarr, J. A. & Mcshane, C. (2008). The Horse as an Urban Technology. Journal Of Urban Technology, 15(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630730802097765

[2] Stull, C. L. (2012). The journey to slaughter for North American horses. Animal Frontiers, 2(3), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2012-0052

[3] Stephenson, R., et al. (1851). DISCUSSION. THE NOMINAL HORSEPOWER OF STEAM ENGINES. Minutes Of The Proceedings Of The Institution Of Civil Engineers, 10(1851), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1680/imotp.1851.24105

[4] Kommer, C., Tugendhat, T. & Wahl, N. (2019). Energie und Arbeit. In Springer eBooks (S. 70–91). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-59396-7_4

[5] Golf 1. Generation (1974 – 1983). (o.D.). Volkswagen Newsroom. https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/de/golf-1-generation-1974-1983-17905

[6] Der Anfang: Golf I – 1974 bis 1983. (o.D.). Volkswagen Newsroom. https://www.volkswagen-newsroom.com/de/40-jahre-golf-2666/der-anfang-golf-i-1974-bis-1983-2677

[7] Fallbeschleunigung im Sonnensystem (o.D.). LeifiPhysik. https://www.leifiphysik.de/mechanik/kraft-und-masse-ortsfaktor/ausblick/fallbeschleunigungen-im-sonnensystem

0 Kommentare